A detailed look at the rich history of the world’s finest Islay whisky, Laphroaig.

Timeline of History:

1810: Two brothers, Donald & Alexander Johnston, leased 1000 acres of land from the laird of Islay, for rearing cattle. That land is now known as Laphroaig.

1815: To raise cattle you must grow “feed” barley for the long winter months. And, what do you do with the surplus barley? If you are English, you ferment beer. But for an Islay Scotsman there is only one thing to do: distil whisky.

The word had spread around Islay that the whisky being produced at Laphroaig was particularly good – their source of water being very soft, peaty and lacking in minerals. It soon became more profitable to distil whisky than raise cattle, and in that year Laphroaig whisky was “officially” born.

1836: Donald offered his brother Alexander £350 for his share of Laphroaig. Alexander agreed, and later emigrated to Australia where he lived to a ripe old age, dying in 1881.

Unfortunately, Donald only lived until 1847. It is believed that he died after falling into a vat of partially-made whisky.

Donald’s only heir was his son, Dugald. At just 11 years old, he was too young to take over, so the distillery was looked after by his uncle, John Johnston, and a local farmer, Peter McIntyre.

1857: By 1857, Dugald Johnston was old enough to take over the running of the distillery himself. He was assisted by his cousin, Alexander Johnston. Together they ran the distillery until Dugald died on 6th of January 1877.

The fame of Laphroaig continued to grow, and new buildings were erected.

However, as was the way in the late nineteenth century, much of Islay’s malt went into blends, and Laphroaig was no different. Its smoky, peaty taste was highly appreciated by whisky blenders. It was especially esteemed by Laphroaig’s next door neighbours at Lagavulin, which was owned by Mackie and Co, Glasgow spirit and blending merchants. Mackie were taking the lion’s share of Laphroaig’s output for blending with grain whisky. This had always troubled Dugald, as it restricted Laphroaig’s ability to sell its own single malt whisky to a wider market.

With Laphroaig gaining more and more of a reputation as a single malt, the problem was now coming to a head.

1887: Alexander died and the distillery was inherited by his sisters, Mrs William Hunter and Katherine Johnston, and by his nephew, J. Johnston-Hunter.

Laphroaig’s fame as a unique whisky continued to spread. In 1887, the leading whisky journalist of the time, Alfred Bernard, reported: “The whisky made at Laphroaig is of exceptional character. The distillery is greatly aided by circumstances that cannot be accounted for… largely influenced by the accidents of locality, water and position.”

The family decided that blenders Mackie and Co were getting too much of a whisky that was in demand as a single malt and terminated their agreement. Mackie and Co reacted by accusing Laphroaig of acting illegally, and took the distillery to court – a case it duly lost.

1907:The battle between Laphroaig and the blenders, Mackie and Co, continued into the early twentieth century.

In 1907, Peter Mackie had the distillery’s Kilbride Stream blocked with stones. With the water diverted, Laphroaig was without a key ingredient and its only source of coolant, and was subsequently unable to function.

Fortunately, the courts quickly intervened and Mackie was required to “put things right” and restore the water supply.

In 1908, in a fit of pique, Peter Mackie decided that if he couldn’t beat us, then he would join us – sort of. With the help of Laphroaig’s head brewer, who he had persuaded to work for him at Lagavulin, he built an exact copy of the Laphroaig still house, hoping to create another Laphroaig.

1921: One might have thought that with Laphroaig’s head brewer, exact copies of the stills, the same bay right next door, and a nearby source of water, it would be easy to copy Laphroaig’s taste. Not so. Such is the delicate alchemy of Laphroaig.

When Peter Mackie realised this, he made two further attempts to buy Laphroaig and its land, but these also failed. Sadly, the cost of all these battles was great, and put a strain on the young company. Still, at least Kilbride Stream, source of the distillery’s water, was secured.

1923: Ian Hunter – son of William Hunter – took over the running of the distillery in 1921 and revitalised it.

Due to the various court cases, money was difficult when he arrived, and Ian had quite a struggle to keep things going, particularly as a new lease was due to be made with the owners, Ramsay of Kidalton. Mackie and Company put in a higher offer to rent Laphroaig. However, everything was eventually straightened out and the owners decided to sell the estate and gave south Islay’s distillers the first opportunity to buy the land. The offer applied to Ardbeg and Lagavulin, as well as Laphroaig. Again Mackie tried to outbid Laphroaig without success. After the completion of the purchase, it was decided to increase the capacity of Laphroaig.

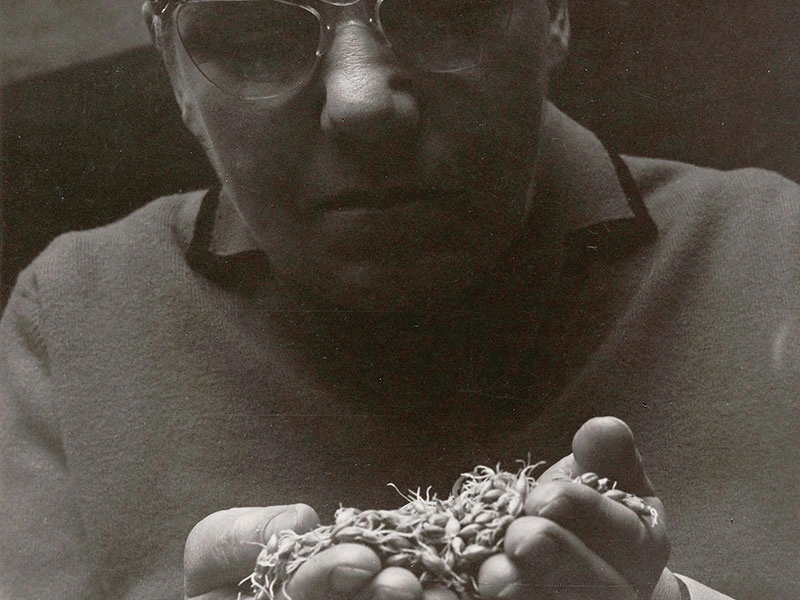

By 1923 the Laphroaig capacity had doubled and the maltings, as they now stand, were completed. A new wash still and spirit still were erected. Ian Hunter being a stickler for detail, they were the exact duplicates of the originals.

1929: Upon taking up ownership of the distillery, Ian literally spread the Laphroaig gospel around the world.

Among the first to fall for its full-bodied, thick peat smoke and oily character were the Scandinavians – perhaps unsurprisingly as they were some of Islay’s earliest settlers. Exports grew to Latin America, Europe and Canada. Even Prohibition America was targeted, Ian managed to persuade US customs and excise that the whisky’s pungent seaweed or iodine-like nose was evidence of Laphroaig’s medicinal properties. According to the way some tell the story, it was after a “wee dram or two” that the customs officers agreed with Ian and Laphroaig was legally exported to America.

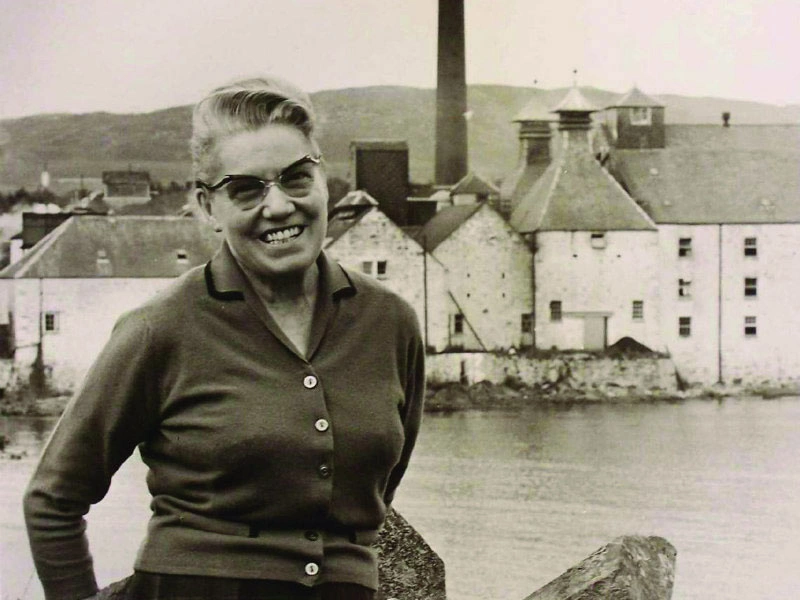

1935: Bessie Williamson left Glasgow University with an MA in 1932. With jobs scarce in the economic slump that hit cities like Glasgow in the early 1930s, she took on a succession of temporary appointments.

In her search for regular employment, she kept in close touch with her uncle Willie, who was an accountant to none other than Ian Hunter at Laphroaig. One summer, Ian wrote to him asking if he knew of a reliable woman for a summer office job. Bessie jumped at the chance and arrived with just one suitcase, for the summer, unaware that it would be 40 summers and the love of a lifetime before she left.

Ian Hunter was the last of the family line. The secrets had been carefully guarded by the family over the years, and Ian was incredibly protective with regards to the distillery, its setup and the whisky’s recipe. He never let journalists, photographers or writers near the distillery, and even took a retired cooper to court to stop the publication of a book that contained a description of the distillery.

However, in Bessie he found a person that had passion, integrity and the drive to maintain the great traditions of this whisky. So, over the years, he passed on to her all the distillery knowledge he had acquired.

It was during this time that Ian’s ideas for maturing Laphroaig’s spirit in ex-bourbon American white oak casks began to properly take hold. The Second World War and local changes, in Spain, in the rules for exporting sherry in casks had resulted in a scarcity of fresh ex-sherry butts. The result was an industry pushed to re-using exhausted casks. Preferring not to compromise the distillery’s high standards, Ian pioneered the use of the more readily available American 53 gallon barrels, which he had broken down and re-coopered as slightly bigger hogshead casks in Laphroaig’s cooperage. By 1950, the majority of Laphroaig’s spirit was laid down in ex-bourbon American oak.

1954: During the war, the Laphroaig distillery was commandeered as a military depot. Ian Hunter was now confined to a wheelchair and had decided that – on his death – Bessie Williamson was the only person that could maintain and develop Laphroaig’s long traditions. He died in 1954, bequeathing the whole distillery to her.

Bessie took the reigns as one of the first female owners and distillers in the industry. A true islander, she strengthened Laphroaig’s close links with Islay life, joining in with the annual peat cutting, singing, and dancing to Gaelic songs at the Saturday night “ceilidhs.” She even opened up distillery buildings for community dances. However, her first love was always Laphroaig, and during her tenure its fame and sales grew.

Bessie was a pragmatist and knew that for Laphroaig to continue to grow worldwide, it needed the support of an international group, one that would continue the old traditions but had the financial muscle to carry the brand through to new global markets. So in the 60’s, she gradually sold Laphroaig to Seager Evans & Co (a subsidiary of Schenley International) via its Scottish asset Long John Distillery. Seagar Evans acquired its first share in 1962 and completed the acquisition in 1967. Seagar Evans would go on to rebrand as Long John International.

Bessie retired in 1972, and died 10 years later. John McDougal, who succeeded Bessie as distillery manager, remembered her most fondly: “It was an honour to work with Bessie Williamson and I will never forget her words of wisdom. They have stood me in good stead the 44 years since she left the office next to mine. So far as I am concerned, she has never left Laphroaig. To have been the last manager to work directly with and for her was an absolute privilege.” Laphroaig owes Bessie Williamson an enormous debt.

Over the course of the 1980s, Laphroaig’s reputation grew. Much of this was down to the stewardship of a clutch of excellent distillery managers. Denis Nicol was succeeded by Murdo Reed, who oversaw the stills being turned 180 degrees and the installation of a new still house roof. In turn, Murdo was succeeded briefly by Colin Ross, before the arrival of Iain Henderson in 1989.

Iain Henderson’s 14-year tenure marked the dawn of a new era, one that saw the inauguration of Friends of Laphroaig, the distillery being granted a Royal Warrant, and Laphroaig awarded a raft of top class awards.

In 1990, Laphroaig’s owner, Whitbread, sold off its spirits division. The distillery was acquired by Allied Spirits, a subsidiary of Allied Lyons, which in 1994 changed its name to Allied Domecq, having acquired the Spanish brandy and sherry giant Pedro Domecq. It was during this time – under the guidance of owner and distillery manager Iain Henderson – that Laphroaig 10 Year Old became the world’s fastest-selling single malt.

1994: Any Laphroaig drinker will know its most famous patron by the distinctive coat of arms carried on every bottle. In 1994, HRH Prince Charles visited Laphroaig for the first time and gave the distillery his Royal Warrant. As well as being found on each bottle, the royal coat of arms is inscribed on the 200-year-old walls of the original buildings. His Royal Highness being the present Lord of the Isles, it is an honour especially fitting for Islay-based Laphroaig.

When here, His Royal Highness signed the Visitors’ Book and spoke with then distillery manager, Iain Henderson, with whom he eventually parted, saying: “I hope you continue to use the traditional methods. I think you make the finest whisky in the world.”

It was also in 1994 that Friends of Laphroaig was officially set up. On joining the Friends, each member is given their own lifetime’s lease of a square foot of land on Islay, alongside the opportunity to claim their annual ‘rent’, a dram of our finest.

2015: We celebrated our 200th year with a whole host of events and special releases. At the request of our Friends of Laphroaig, we released a one-off bottling of the 15 Year Old, last brought out as the Erskine Charity Bottling in 2000. In May, the Feis Ile saw the launch of a 200th special Cairdeas bottling, a very limited 32 Year Old and a 21 Year Old, a FoL birthday exclusive. In July, we were graced with our third visit from HRH the Prince of Wales, who launched our Legacy Fund for the islanders. In 2015, the 200 winners of our Opinions Welcome competition had their opinions inscribed on the distillery wall.